Innovation is a particularly sticky problem because it so often remains undefined. We treat it as a monolith, as if every innovation is the same and one approach fits all. That’s why efforts tend to be fraught with buzzwords and rarely lead anywhere. With all the confusion, how should we go about innovation? Should it be handed over to guys with white coats in labs, an external partner, a specialist in the field, crowd-source or what? Defining the innovation problem is often overlooked, but it’s absolutely essential if we are to choose the right path. Here’s a framework that will help.

Innovation Matrix

-

April 21, 2015

- Posted by: rodasa

INTRODUCTION

DEFINING INNOVATION CATEGORIES

Innovation is a diverse activity. In laboratories and factory floors, universities and coffee shops, or even over a beer after work, people are looking for better ways to do things. There is no monopoly on creative thought. However, we do need to be careful, because there is a big difference between a random brainstorm and a concerted effort. Innovation as an organized practice falls into four categories:

- Basic Research: This is the type of work done at universities and some R&D labs. There isn’t a clearly defined outcome. The point is to discover more about how things work. Some say that basic research isn’t innovation, because it does not necessarily result in a new product or service, but I disagree. It would be tough to argue that people like Einstein or Watson and Crick weren’t innovative. They revolutionized their fields. Moreover, basic research pays huge dividends in the long term and it’s difficult to imagine our modern world without discoveries which seemed useless at the time.

- Sustaining Innovation: This is the type of innovation that Apple excels at, where there is a clearly defined problem and a reasonably good understanding of how to solve it. When Steve Jobs first envisioned the iPod, it was simply a device that allowed you to put “1000 songs in your pocket.” That meant you needed to have a certain amount of memory fit into certain dimensions. Those were difficult problems that took a few years to solve, but it was pretty clear what was involved and who was capable of solving them.

- Disruptive Innovation: Clayton Christensen introduced the concept of disruptive innovation in his classic book The Innovator’s Dilemma. These tend to be new approaches to old products and services. I’ve referred to disruptive innovation in the past as crappy innovation, because it tends to perform poorly on previously defined parameters (like early digital cameras that took lousy pictures), but outperform on a different parameter, such as price or convenience or compatibility.

- Breakthrough Innovation: Thomas Kuhn called this “revolutionary science” because it involves a paradigm shift. In this case, the problem is well defined, but the path to the solution is unclear, usually because those involved in the domain have hit a wall. Transistors and the discovery of the structure of DNA are both good examples of breakthrough innovation.

BUILDING A MATRIX

Upon a little reflection, it should become clear that different types of innovations address different types of problems. Some problems, like the iPod or the structure of DNA, are well defined. Others, like digital cameras (who knew they wanted one until they existed) and discovery of extraterrestrial life (maybe someone’s out there, maybe there’s not), are a bit more nebulous.

There is also variance in who is best positioned to solve problems. Sometimes you want someone with deep experience in the domain, sometimes an outsider. Conventional disc drive manufacturers were able to solve Steve Jobs’ iPod problem, but companies who make billions on oil are not likely to come up with innovative solutions for alternative energy.

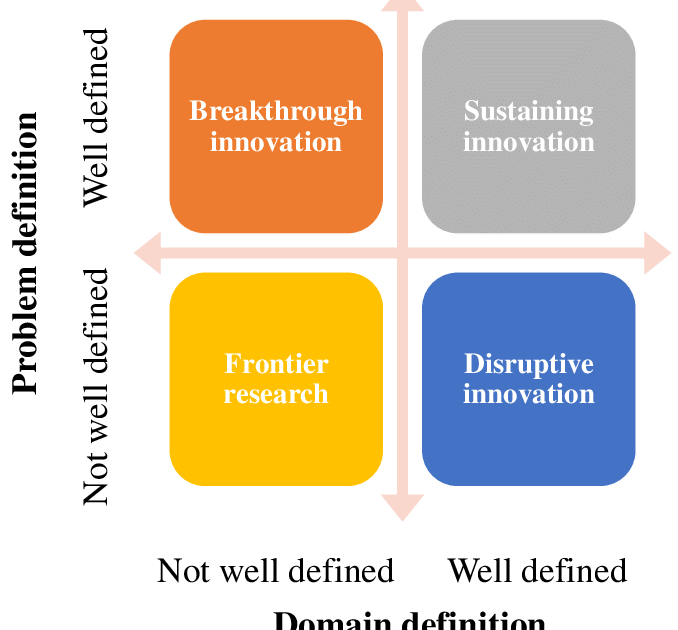

By putting the parameters of problem definition and domain definition on two separate axes, we can form a matrix that the four types of innovation fit nicely into:

This gives us a good basic framework for determining what type of innovation we might want to pursue. Sometimes, we have well defined problems, sometimes we don’t. Sometimes it’s clear who is best equipped to tackle a problem, sometimes it isn’t. By asking ourselves those two questions, we can outline a successful approach.

PARSING SOLUTIONS

Just as there are different types of innovation, there are number of ways that companies can pursue innovation. Once we have defined the innovation problem, mapping solutions onto the matrix is fairly straightforward:

- Basic Research: While basic research rarely leads directly to new products or services, many corporations invest serious money into it. Some companies, like IBM, have internal labs doing primary research, while others invest by way of research grants to outside scientists and academic affiliations.

- Sustaining Innovation: Sustaining innovation is probably the most common in the corporate world and is often referred to as engineering rather than science. Like basic research, much of this is done by internal R&D labs, but many firms outsource it as well.

For instance, when Steve Jobs wanted a mouse for the Macintosh computer, he went to IDEO with clear technical specifications knowing that they had the right skills to produce what he wanted.

- Disruptive Innovation: Disruptive innovation is particularly tricky because you don’t know it until you see it and sometimes its value isn’t immediately clear. That’s why venture capital firms expect the vast majority of their investments to fail.

There is also a growing trend toward corporate innovation labs, which work closely with start-ups to perform ongoing “test and learn” programs that help identify promising new technologies before they are fully mature.

- Breakthrough Innovation: Often, a particular field has trouble moving forward because they need a new approach. That’s why breakthroughs often come from newcomers. Einstein and Newton were both in their 20’s when they came up with their major discoveries. The problem is, of course, waiting for a maverick genius to come along isn’t an efficient solution.

One way companies have started to attack the problem is through open innovation, either through internal programs like P&G’s connect and develop or through external platforms such as Innocentive. As Jonah Lehrer points out in his book Imagine, answers to tough questions often come from professionals working outside their chosen field.

Finally, some companies build multidisciplinary teams and set them up in a separate unit to pursue a particular innovation, like IBM did when they created the PC. This is rare, but can be the only viable option when breakthrough innovation is crucial to the future of a business.

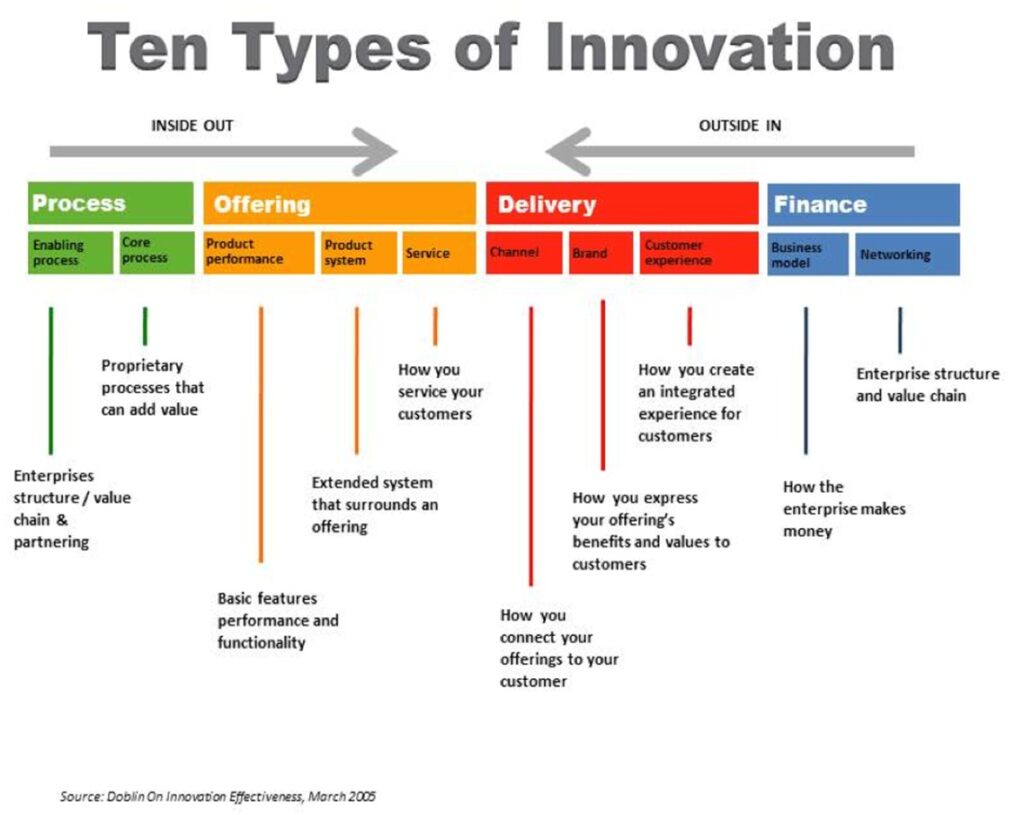

TEN TYPES OF INNOVATION

The Ultimate Innovation Decision

Probably the toughest thing about innovation is deciding what to do about it. From changing the organizational structure and compensation logic of a business, to pricing and partnering strategies to new products and services, every facet of every business is ripe for innovation.

Deciding what to do about it is the #1 problem. Should you rely on a direct manager to innovate? After all, she knows the subject best. Should you bring in a whip-smart consultant? Talk with an academic? Partner? Crowdsource? What? The variety of options is not only dizzying, it’s paralyzing.

I think this matrix can help. Once you have answered the two basic questions of how well the problem and the domain are defined, your options drop precipitously, providing the clarity that can lead to action.

To paraphrase, Voltaire, if you need to solve a problem, first define your terms.